The Star-Spangled Banner

A pivotal piece of American history is restored in the nation's capitalIt was with the same respect for the story told by the wear and tear on the flag that conservators at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History approached the preservation of one of America’s most cherished scraps of fabric: the Star-Spangled Banner. You can’t see the hard work, but nearly a decade of effort went into preserving its famously tattered state, immortalized by Francis Scott Key in the song that gave the flag its nickname. And according to Jim Gardner, the museum’s former associate director for curatorial affairs, that’s the point. “Our goal was not to restore the flag but to preserve it for generations to come,” he says.

In 1998, the flag was taken down from the wall where it had hung since 1964. A lengthy evaluation process involving 50 international experts—conservators, curators, historians, engineers, and organic scientists—helped determine how best to proceed. Technicians began by clipping 1.7 million stitches to remove the linen backing that had been sewn on in 1914. Next, debris was removed with the aid of cosmetic sponges, and the surface was bathed in a mixture of water and acetone to clear away harmful residues. Finally, a new backing, made from a silklike fabric called Stabiltex, was sewn on. The end result has been viewed by millions of visitors to the museum since 1999.

–Ralph Lauren, in his foreword to the book

The Star-Spangled Banner: The Making of an American Icon

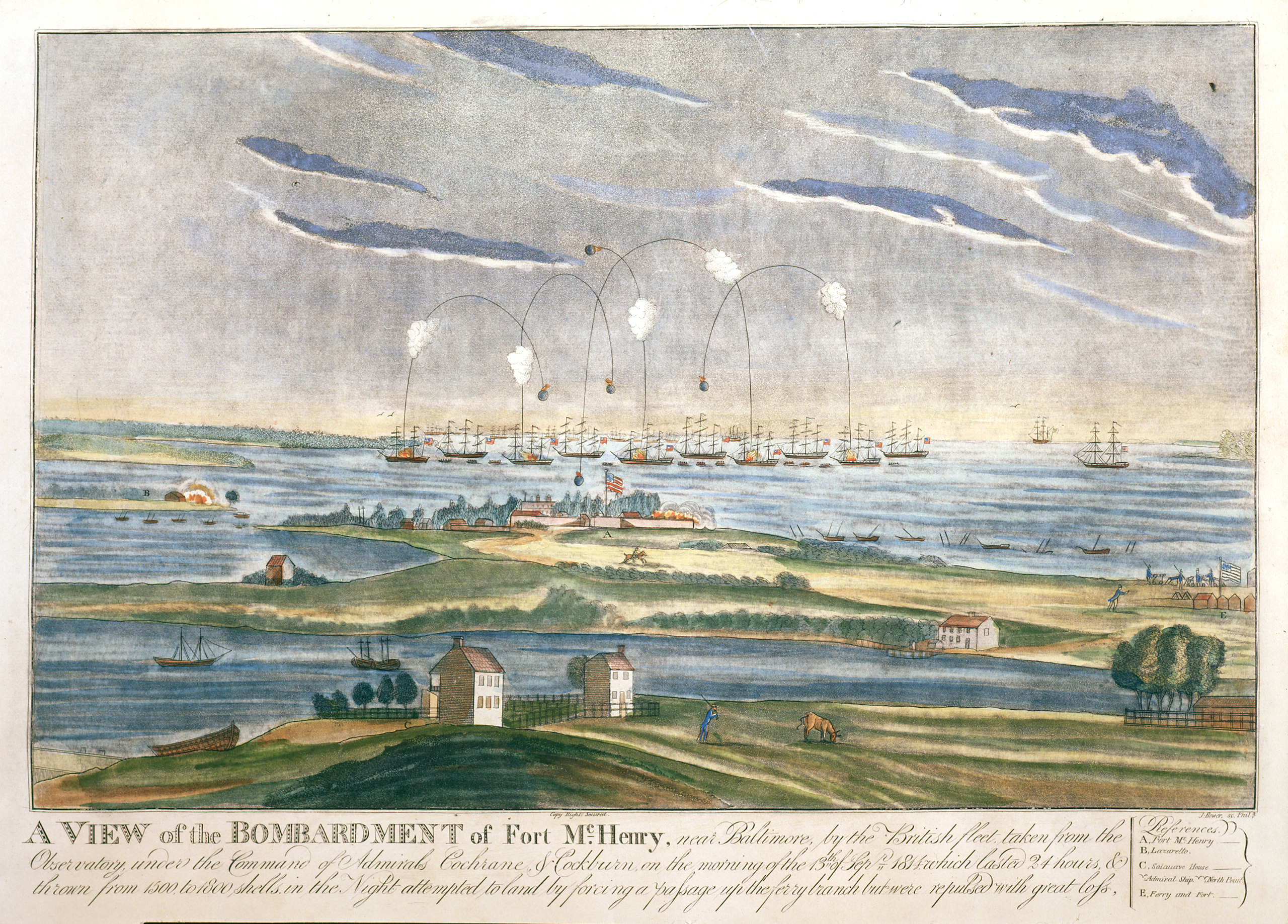

The flag originally featured 15 stars and 15 stripes, reflecting the number of states mandated by the Congress of 1794, and measured 30 feet by 42 feet—large enough to have been seen flying from a 90-foot flagpole at Fort McHenry, in Maryland. It was crafted by Mary Pickersgill, a professional flag maker from Baltimore, for a fee of $405.90, quite a lucrative job at the time. The flag was flown on September 13 and 14, 1814, during the pivotal Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812. Francis Scott Key, a lawyer anxiously watching the battle from an American ship, was inspired to write a poem when, after the siege, he looked toward the fort and saw the flag still waving. Today, the Star-Spangled Banner measures approximately 30 feet by 34 feet—the loss is the result of damage during its service at Fort McHenry, as well as the practice of visitors to the fort taking snippings as souvenirs—and is missing one star.

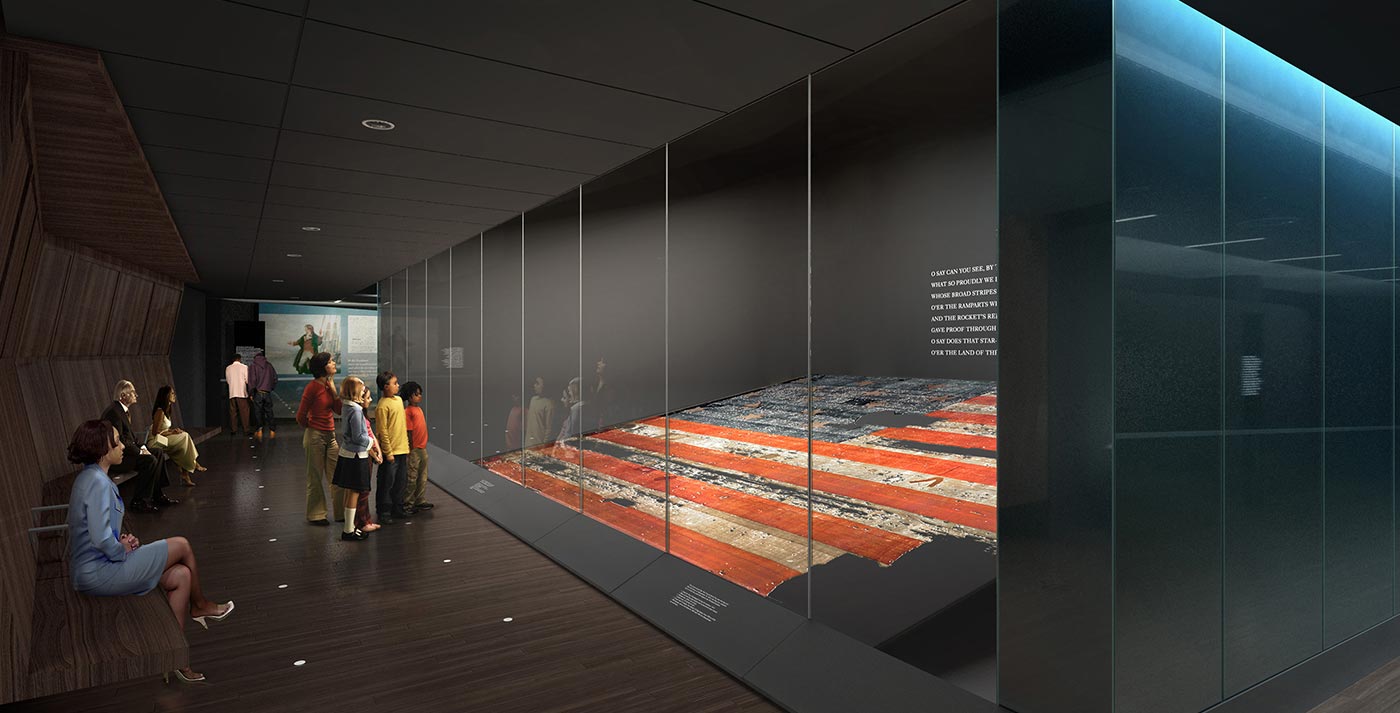

To preserve the flag’s delicate fibers, a special gallery was constructed as part of the Smithsonian’s renovation in 1999. According to then project manager Jeffrey Brodie, the engineering and construction of the flag’s new chamber took nearly as long as the delicate textile conservation, and the room is designed to provide “the best conditions [the flag] could possibly have.” The level of light, the temperature, and the humidity are carefully controlled.

The invisible accommodations, however, tell only half the story. Another aim of the new, permanent display, says Brodie, is to present the flag within its historical context. In September 1814, he says, the United States was “a fledgling nation, struggling for its own economy, struggling to establish itself in a Europe-dominated world. The British had just burned the White House and the Library of Congress, sacked [Washington, DC], and left for Baltimore, where they met with great and fierce resistance.” The exhibition’s introduction explains the perils of the times through historical weapons, such as bombs and rockets, and a piece of charred White House timber. But the main attraction receives a decidedly subtler treatment. A long corridor allows visitors’ eyes to gradually adjust to the darkness before the flag, displayed horizontally in a glass case, materializes as if seen by “dawn’s early light.”

Gardner says, “The goal is to have everything else disappear in that room and just have the flag there, glowing, with [Key’s] verse.” If that sounds dramatic, well, it’s meant to be: When Key penned his anthem, “the fate of the new nation was at stake, and that flag represented a critical moment in the nation’s history,” says Gardner. “You could say that the American Revolution achieved independence, but 1814 was when it was secured for the future.”

- All photographs courtesy of the National Museum of American History