Having a Ball

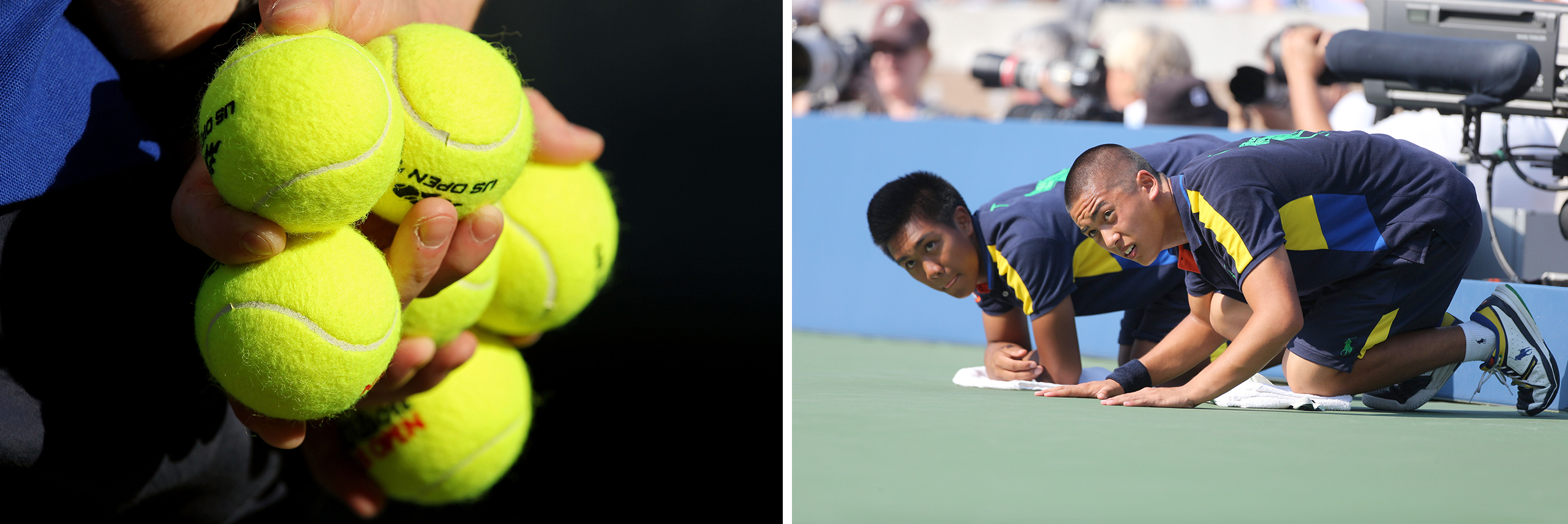

Some of the best athletes at the US Open never actually swing a racquet. As Scott Christian discovered, joining the ranks of the US Open ballpersons takes agility, enthusiasm—and a great arm.Like little green rockets, three tennis balls zing overhead in quick succession. The first narrowly grazes Court 11’s waist-high chain-link fence as it comes down, landing just in front of the bleachers and then skittering to a stop in the middle of a walkway at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. The second ball clears the fence completely, disappearing under a distant hedge. And the third one? Well, let’s just say that a weather eye is a necessity when the teenager winging balls across the court has more strength than accuracy, a lesson unfortunately learned by a photographer, who will spend the rest of the US Open ballperson tryouts nursing a lump on her forehead.

Of course, good aim is only one attribute that Cathie Delaney, assistant director of ballpersons for the US Open who’s been running the US Open ballperson operation along with US Open Director of Ballpersons Tina Taps for about 25 years, looks for. Every June approximately 400 ballperson hopefuls spread out across seven courts of the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in Flushing, Queens, New York, to sprint, roll and collect balls in a variety of drills meant to simulate the conditions of a professional tennis match. Evaluating those hopefuls, and making the first round of cuts (there are two rounds, plus an interview), are a group of ballperson veterans selected by Delaney and Taps.

The tryouts themselves begin in earnest during the late afternoon, a few hours after the press have had their chance to sweat and huff their way through the process. First, initial instruction is given to the assembled crowd on Court 11, in the shadow of Flushing’s iconic Arthur Ashe Stadium. Then, as the majority of the blue-T-shirted prospects disperse onto six other nearby courts, the proceedings officially commence, stirring up a kinetic heat that adds to the already balmy conditions of the June afternoon. The drills performed will showcase the aspiring ballperson’s skills as they try out for a position either at net or at back-of-baseline. Some, however, will do both.

Unsurprisingly, for most the audition process is a nerve-racking affair. For those who were athletic in high school, it may inspire sweet notes of nostalgia, but for those who weren’t, it’s more likely to bring about pangs of post-traumatic stress. Though Delaney is an upbeat person who clearly loves her job, she is still a coach, and has something of a drill sergeant in her. And like a good coach, her authority flows from her pupils’ desire to impress her. Although she doesn’t actually do any evaluating during the first round of tryouts—she leaves that to supervisors, who also hit balls and generally keep the show running—she does notice the standouts.

For those trying out for both positions, each takes a turn at net, and then at back, or vice versa. The net position involves sprinting back and forth, collecting stray balls and rolling them accurately back to the back-of-baseline. It’s a job that requires agility, excellent hand-eye coordination and a strong lower back because of the amount of crouching involved. For back-of-baseline, it’s all about catching and rolling. The primary drill is to roll three balls in quick succession across the court to the ballperson in the other back position. The ball has to arrive accurately (without hitting any civilians). Those on the receiving end are tasked with collecting the balls.

As for the rest of the tryouts, within 15 minutes of the start, everything around the tennis center becomes organized chaos. Teenagers who’ve finished their drills spill out onto the walkways and bleachers, chattering about their successes and failures. A trickle of stray tennis balls begins to accumulate along the edges of the courts, remnants of errant steps and failed catches. The added distraction is not entirely unwelcome, though, as it can help simulate the Sturm und Drang of the actual event. The ability to remain composed under pressure is an important attribute for any successful ballperson. Delaney wants to know that her rookies aren’t going to freeze up the moment the first ball is served in an official match. “I’ve seen kids who think they know the game become clueless,” she says. “Like a deer in the headlights.”

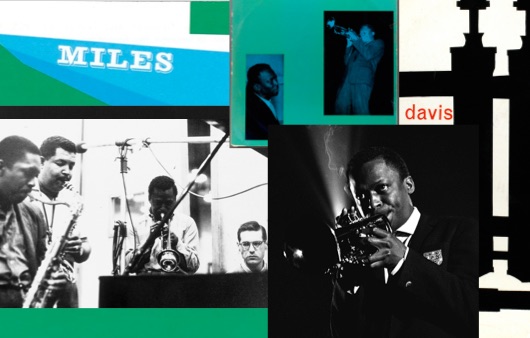

Ultimately, the goal of a ballperson is to be “integral but invisible,” says Dorian Waring, who has been a ballperson for more than 20 years and works as a supervisor for both the tryouts and the main event. It’s a philosophy that dates back to the first-ever ballboys, who were introduced at The Championships, Wimbledon, in the 1920s. Before that, players chased around their own balls, inevitably delaying the game. To speed things up, the Wimbledon organizers recruited boys from Shaftesbury Homes and Arethusa—a charity that at the time established residential schools for poor children—to do it for them. The idea was that a six-boy crew would keep the game running smoothly while essentially blending into the background. It worked so well that the rest of the Grand Slam tournaments eventually adopted it.

These days, the US Open still features a six-person crew with two at net and four at the back-of-baseline position, working to wrangle tennis balls. Most important, it is a job performed while leaving as little of a footprint on the game as possible. “The worst moment for any ballperson is hearing the umpire say, ‘Wait please,’” says Wendy Baum, a 25-year veteran who supervises during the US Open and works the occasional match as well. “Yeah,” Waring agrees, “you make that mistake once and then you never make it again.”

According to Guinness World Records, the oldest ballperson ever to take the court in a major tennis championship was Manny Hershkowitz, who, in 1999, worked the US Open at the tender age of 82. Most of those trying out, though, are teenagers. The minimum age to be a US Open ballperson is 14, and many, but not all, of the hopefuls are around 16 years old. Erica Vercessi, who turned 14 this year, is trying out for the first time after watching her brother shag balls for three years. Although she is fairly typical of the demographic, her preparation method probably isn’t: She watched a Late Night video of the show’s former host Jimmy Fallon trying out in 2009.

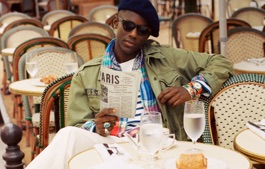

For some, though, ballperson tryouts are a bucket-list activity. Take James Lisa, who, at 28, after moving to New York from Delaware three years ago, decided it was time to give the tryouts a shot. “It’s just one of those things I’ve always wanted to do,” he says, blending in more with the parents than with the kids trying out. But that’s the great thing about being a ballperson; age doesn’t matter nearly as much as enthusiasm and ability. “We want people who love tennis,” says Delaney. “But we also want people who are enthusiastic, and who just want to be part of this great event.”

- Photographs by Weston Wells