One Man Is an Island

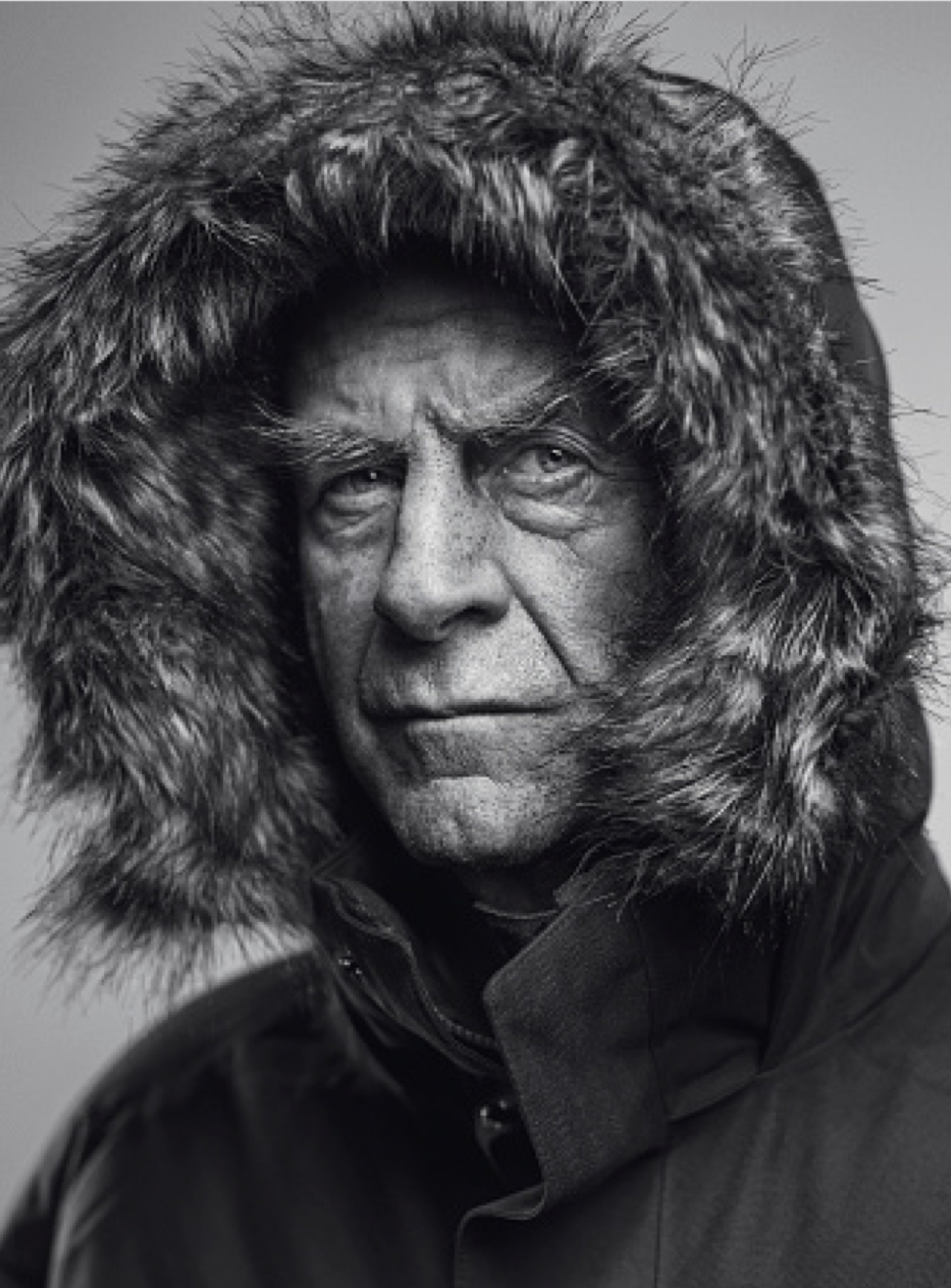

He has persevered in extreme environments for nearly half a century, leading journeys to the polar regions and elsewhere that have tested the limits of human endurance. He has also written some 30 books, including a new biography of Lawrence of Arabia. Just don’t call him Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-FiennesThe exploring career of Ranulph Fiennes has brought him armfuls of honors, records, book deals, lecture contracts, film projects, and admiring fans. Fiennes, though, is not the only figure to have benefited from these efforts. His work has restored the fading image of the old-school British explorer, a traditional figure that Fiennes has arguably done more than anyone to maintain.

Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, as he hates to be called, seems to hail from another era. In one literal sense, he does: Many of his major feats were achieved before the advent of satellite phones and GPS. But “Ran Fiennes,” as he prefers to be called, is also a throwback in other ways. He’s proudly and brusquely British; an Eton-educated baronet; a third cousin, once removed of the actors Ralph and Joseph Fiennes; and an unofficial custodian of the nation’s stiff upper lip. Competitive overland polar travel peaked more than a century ago, but don’t tell the 79-year-old that: Fiennes appears to consider “the Norwegians” as serious a threat to British primacy as his Edwardian forebears did.

As others have pointed out, Fiennes is a bit of a nutter. King Charles, a longtime supporter of his exploits, has called him one of the “great eccentrics”—and not of the silly hat variety. Following a failed solo North Pole attempt in 2000, Fiennes sawed off four of his painfully frostbitten fingertips rather than wait for surgery. As he later explained in a memoir, he wanted to go back to putting his own neckties and cuff links on. When the dead fingers later went missing from his desk drawer, Fiennes asked readers of The Times of London for help in finding them. They have yet to turn up.

Recently reached by phone—a landline, naturally—at his farm in Exmoor, a half day’s drive west of London, Fiennes speaks about his unusual career path (which includes, many years ago, nearly being chosen to replace Sean Connery as James Bond) in strenuously matter-of-fact terms. The books and talks resulting from his outlandish journeys are simply how he pays the bills, he says, and he has suggested that his profession is less dangerous than commuting on British motorways or taking beach vacations which can, after all, cause skin cancer. Is Fiennes serious? One can’t be wholly sure. He once claimed his favorite song was Enya’s “Orinoco Flow.” Until recently, he drove himself to his lectures in a battered Ford station wagon, which he also slept in, despite the extreme likelihood that he could afford hotel rooms.

Fiennes does less driving now—less of everything, really. “I have the ravages of old age,” he admits. His feet are destroyed; his memory is going. When Fiennes was 59, he ran seven marathons in seven continents in seven days; now, 20 years later, he hopes to squeeze “a modicum of exercise” out of his unwilling body. He makes no bones about his physical decline or how much it frustrates him. “One thing I find really annoying is getting deaf,” he says. “Then, of course, you’re frightened of your wife”—he raises his voice—“‘Stop saying what?!’”

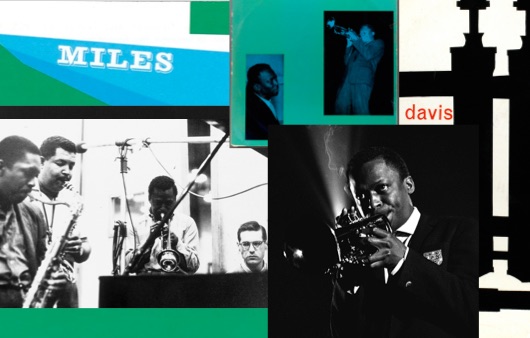

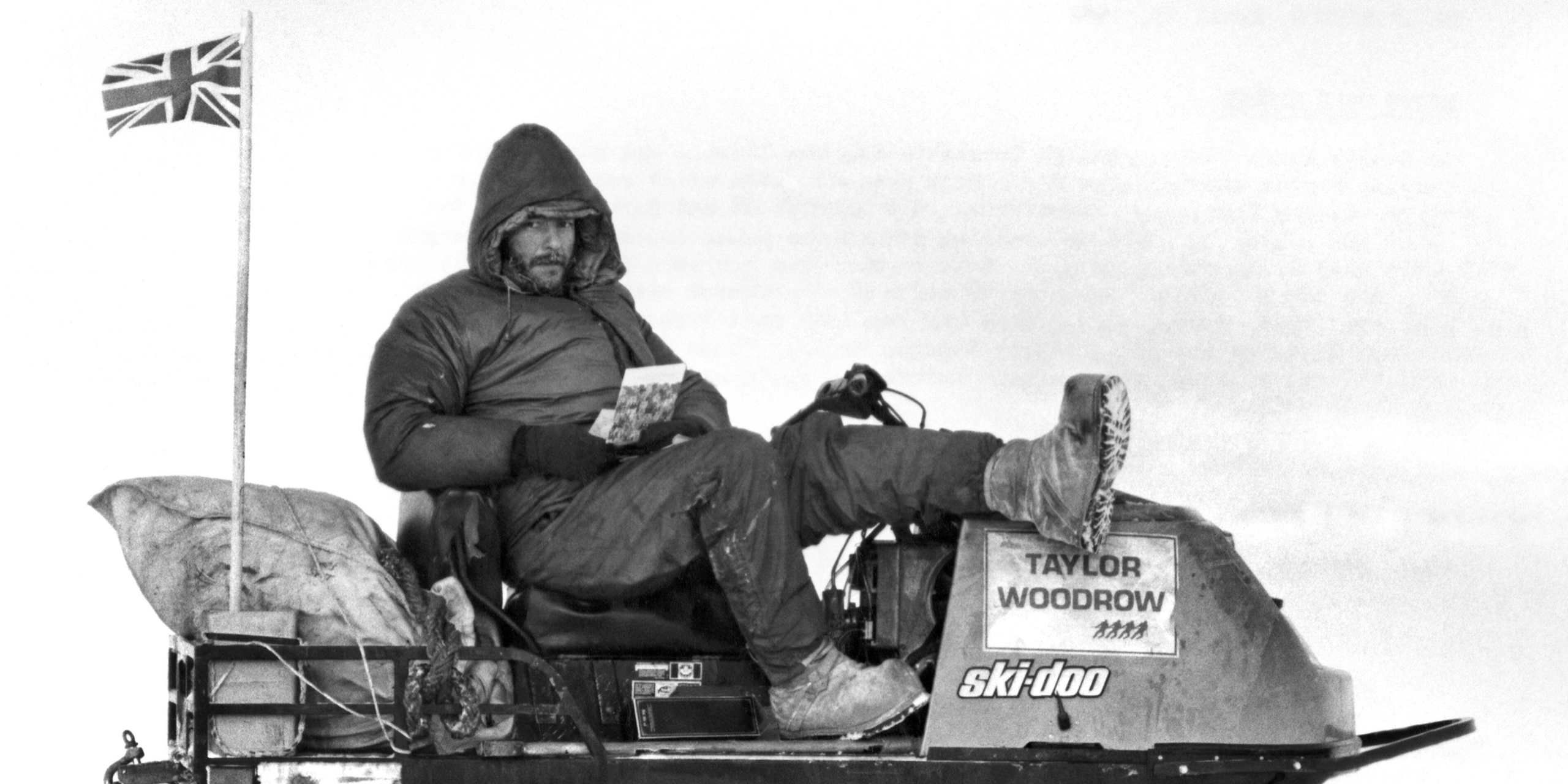

Ranulph Fiennes (top) returns home in 1982 from the Transglobe Expedition, the first attempt to make a circumpolar navigation of the Earth, and (above) a portrait of Fiennes taken in 2016

A photograph Fiennes took at Scott Base, South Pole, Antarctica, 1979

Charles Burton and Fiennes in the arctic darkness

Fiennes reaches the North Pole in 1982

Carving out a cave for temporary shelter

Burton and Fiennes trek across an arctic wasteland

Back to Antarctica in 1992

One thing that Fiennes still does with gusto is write books. (His next one—his 29th or 30th, he can’t say for sure—is Around the World in 80 Years, a sort of personal highlight reel of travel stories whose publication in March will coincide with his 80th birthday.) Since late middle age, Fiennes has also been writing biographies of great explorers, with notes from his own relevant experiences woven in. The first of these was an angry rebuttal of the polar historian Roland Huntford’s unflattering reconsideration of Robert Falcon Scott, the British explorer who arrived at the South Pole just weeks after its discovery in 1911 by Roald Amundsen, who then perished alongside four companions on the journey back. Huntford’s revisionist take was “full of lies,” Fiennes insists. “I hated it. I could tell the lies because I’d done what Scott did.” Three years ago, Fiennes published a biography of the less controversial Anglo-Irish explorer Ernest Shackleton.

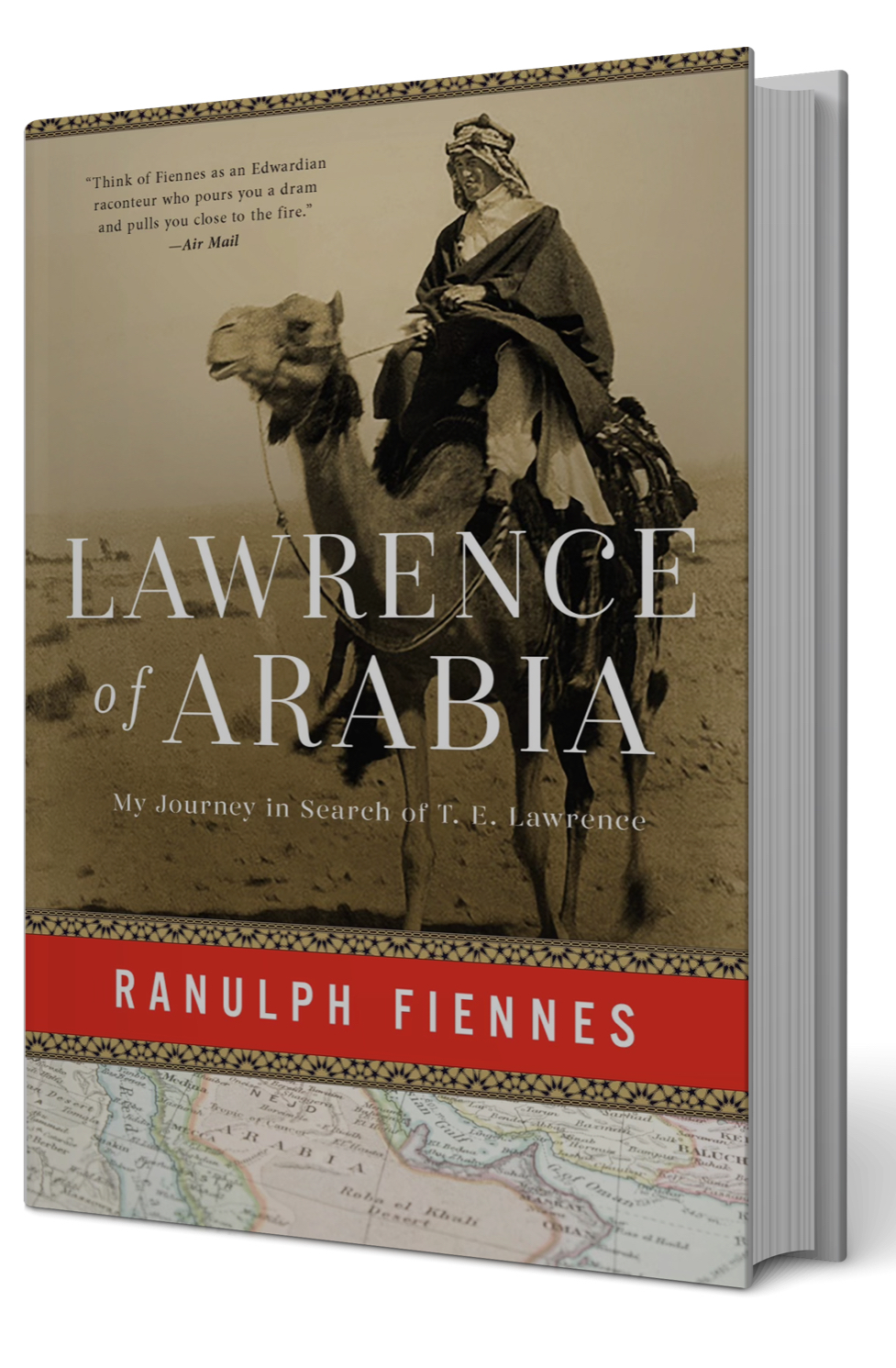

His latest contribution to the genre, out in the United States this month, is a life of T.E. Lawrence, the soldier-scholar and unlikely co-architect of the 1916–1918 Arab Revolt against the German-allied Ottoman Empire who was later immortalized by Peter O’Toole on film. The book, titled Lawrence of Arabia: My Journey in Search of T.E. Lawrence, is mostly a battlefield biography, full of incident and lightly peppered with the author’s memories of the two years he himself spent as a soldier in the Arabian Peninsula.

Fiennes has written some 30 books, including his latest, a biography of T.E. Lawrence

His time as a soldier was in 1967–1968, before Fiennes had ever hitched himself to an Arctic sled. He was a young officer in the Special Air Service (the British Army’s special forces unit) and hungry for action. “I was bored stiff and, at 23 years old, already wondering what on earth I was going to do with the rest of my life,” he writes in the introduction. Given the opportunity to fight a Soviet-backed Marxist insurgency in Oman, and with images of O’Toole’s Lawrence dancing in his head, he volunteered immediately.

Differences between the two men and their respective scenarios abound, but both Britons managed Arab fighting forces, and both had an evident knack for explosives. Fiennes can—and in the book does—personally relate to Lawrence’s haunting first experience of killing an enemy at close range.

Like the geopolitical legacy Lawrence and his countrymen left behind, the man himself was a complex case; behind the Hollywood image of him charging across the dunes in white-and-gold robes lies a tortured individual with a heavy backstory. Fiennes brings a military terseness to his treatment of both. When I ask him about Lawrence’s rebel streak, he rephrases the question in simpler terms: “He annoyed senior officers and enjoyed annoying them.” Was Fiennes the same with his superiors? “Not all of them but some of them, yes,” he says. His treatment of Lawrence’s much-discussed sexuality is cursory. “Whether or not [Lawrence and his teenage companion Dahoum] enjoyed a sexual relationship—it is now impossible to say,” Fiennes writes. “Judging from the evidence available, it is clear that Lawrence struggled with his homosexuality.”

Unlike Lawrence, Fiennes became interested in the Middle East only after being sent there by his government. He subsequently would return to the region eight times in search of the lost city of Ubar; he and his first wife, Ginny, were part of the expedition that eventually located its ruins in the so-called Empty Quarter of southern Oman. He titled his 1993 book about this escapade Atlantis of the Sands, a sobriquet borrowed from Lawrence.

Fiennes’ decades-long professional partnership and love affair with Ginny, who died in 2004 of stomach cancer, is a primary theme of Explorer, a new feature documentary about him. Seeking to explain his extraordinary drive, the film investigates psychic terrain that Fiennes talks about only sparingly. Both the father he never knew and his grandfather died on the battlefield, which left Fiennes to be raised by his mother and grandmother in South Africa and appears to have set him on an endless quest to impress the ghosts of his male forebears. His early upbringing left him unprepared for the bullying he suffered at Eton, another possible source of lifelong motivation.

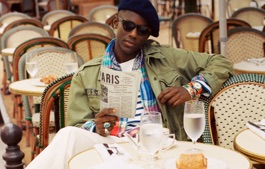

Fiennes, like Lawrence, found the Middle East alluring. He returned there eight times in search of the lost city of Ubar, the Atlantis of the sands

I came away from the film believing that Fiennes’ most punishing decade was his 60s. He was into retirement age when he conquered the treacherous north face of the Eiger, despite a left hand of finger stubs and limited climbing experience. A thousand feet from the top of Everest, he suffered a massive heart attack, and then, four years later, succeeded in summiting the world’s tallest peak, at the age of 65. Fiennes admits that he took on these borderline-insane challenges to escape his grief—the sense, as he puts it in the film, that life without Ginny was “completely second-rate.”

When I ask Fiennes if he’s got advice for anyone wishing to embark on a career like his, he replies that he never set out to become an explorer. He’d always wanted to be a colonel in the Royal Scots Greys, his father’s elite cavalry regiment. His book on Lawrence is, in part, about what he did once his poor academic record put that dream out of reach.

Unlike the intellectually gifted yet romantically challenged Lawrence, Fiennes was warmed by the fire of a nearly lifelong love affair, claiming he never would have taken, let alone envisioned, his explorer’s path had it not been for Ginny. “That was entirely my late wife,” he says.

It’s not what you expect to hear from this apparent island of a man, this avatar of the stoic British explorer’s mindset. Is, I press, this the advice he would offer, then—to find and hold onto a copilot like her? “I wouldn’t disagree with that at all,” he says.